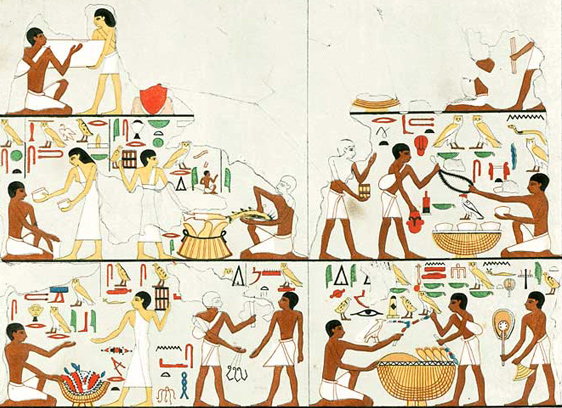

Figure 5: (a) A scene from the tomb of Sobekhotep, a senior treasury official of the reign of Thutmose IV. Africans bring gold rings and rough nuggets from Nubia.[73] (b) Silver rings, silver scrap and a crude ingot, a part of a hoard found in a jar at Tell el-Amarna. The third ring from the left just below the ingot shows an incised design, perhaps a way to ensure the integrity of the ring.[74]

During the development of coinage, it was necessary to ensure and secure the integrity of coins from paring of metal. For this reason coins of precious metals came to be milled along the edge. The application of such a procedure may not have been possible in the case of metal rings and even if it did happen, it would have been unsuccessful. This would have certainly resulted in the metal being weighed in commercial transactions. There appears to be attempts to protect the integrity of rings in ancient Egypt. Three metal rings in the Tell el-Amarna hoard were reported to have had incised designs on their ends [Figure 5(b)].[75]

The integrity of the gold, silver or copper rings (of deben or sh‘t) would have been difficult to maintain against dishonesty and the need of fractional values (i.e., kite) must have resulted in much weighing. In other words, it would have been no longer possible or necessary to maintain the fixed weight of the rings. The standard was maintained by weighing. Weigall has shown several inscribed examples of weights from ancient Egypt of this standard.[76]

It appears that the use of metal rings for trade was quite wide-spread. Metal hoards containing open rings and scrap similar to that from Tell el-Amarna have been found at Ugarit,[77] and in one case it was rings and scrap of electrum.[78] Sollberger has also noted the use of silver rings in Ur III texts and suggested that "the rings in question would be similar to those helicoidal rings well-known from North-European tombs of the early Middle Ages. Payments of gifts could be made by cutting off pieces equivalent to the desired amount."[79]

However, the most dramatic evidence of use of rings for trade comes from Mesopotamia. Powell has drawn attention to the fact that metals were traded in Mesopotamia in a form denoted in texts by Sumerian har, corresponding to Akkadian ewirum (or emerum, semerum).[80] He proposes that these words indicate a circular object. They do not simply mean "ring" in the usual sense, but may refer to a coil of metal, a convenient form in which metals were handled and used for monetary purposes [Figure 6]. Castle points out that this corresponds closely to what has been mentioned about Egyptian deben, as to both etymology and usage.[81]

Figure 6: Silver coils from Mesopotamia used as "money" for trade.[82]

Powell's suggestion is also supported by Old Akkadian text cited by The Assyrian Dictionary Of The Oriental Institute Of The University Of Chicago.

semeru: ... paid five (silver) coils, the price of twenty sheep...[83]

Just like Egyptian deben and sh‘t, the nominal value of these rings may not correspond exactly to their actual weights as given in the texts. This is not a cause of difficulty since they would have been weighed in handling during commercial transactions.[84] To conclude the discussion with Castle's study on trade in Ramesside times:

... clear that precious metals were handled as both scrap and in the form of helcoidal rings throughout the fertile crescent, and that they were used as a form of currency quite early in Mesopotamia, and in Egypt certainly by the New Kingdom Period, and probably earlier.[85]

WHAT IS IN THOSE BAGS TIED BEHIND THE SHOULDERS?

Another piece of evidence of early coinage in ancient Egypt, albeit indirect, often not mentioned, are the market scenes.[86] Perhaps the most conspicuous feature in the market scenes is, without doubt, the presence of men carrying small linen bags thrown over their shoulders, something akin to a purse [Figures 4 and 7]. This feature is attested in many of the market scenes from the Old Kingdom Period onwards. The colour of the bag over the shoulder is usually white. The question now is what could these bags or purses have contained? There is a debate among egyptologists as to what purpose these bags served.

Figure 7: Mastaba depictions of market scenes from 4th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom Period showing the traders with small linen sacks tied behind their shoulders.[87]

It is clear that these bags could not have been used to bring the wares to the market. Men having the bags thrown over their shoulders are represented as buyers as well as sellers. Hodjash and Berlev distinguished two types of scenes: the market scenes where victuals are sold, only the buyers have bags and the scenes where manufactured goods are sold, the sellers are the ones with the bags.[88] This also enables to draw a distinction between those who buy and those who sell. Hodjash and Berlev are of the opinion that the bag over the shoulders served as a receptacle to keep the money and valuables in, something like a purse, even though they doubted if metallic money existed in the ancient Egypt.[89] Since deben and sh‘ty made from precious metals were used in commercial transactions in ancient Egypt, it would not surprising to see them handled in small purses.

SELLING OF JOSEPH IN EGYPT IN THE QUR'AN, TAFSEER AND THE BIBLE

It was mentioned earlier that the Qur'an described the sale of Joseph as darhima maddatin. Al-Zamakhshar in his al-Kashshf says concerning the phrase darhima ma‘ddatin:

{sharawhu} They sold him {bithamanin bakhsin} for less than the due price so obviously [...] {darhim} that is, not dinrs {maddatin} so few they were countable and were not weighed. Indeed, they would not weigh amounts less than an uqiyyah which is equal to 40 dirhams and would count any amount below that (limit). Moreover, small amounts are qualified as maddah, since large amounts cannot be (easily) counted. It was narrated on the authority of Ibn ‘Abbs that: (the price) was 20 dirhams. According to al-Sudd: It was 22 dirhams. [...]

Similarly, al-Tabari says in his Tafseer:

The correct stance about this is to say that: Allah Almighty mentioned that they sold him for a few dirhams, counted not weighed, without disclosing the exact amount neither in weight nor in count. Neither did He provide any indication in this regard whether in the Book or in an account through the Messenger - peace be upon him. The price may be 20 dirhams, or 22 dirhams, or 40 dirhams. It could be more or less than that. Whatever that amount was, it was counted not weighed. Neither does the knowledge of the exact amount bring any benefit, nor does the lack thereof bring about any harm religionwise. We are ordered to believe in the apparent intent of the revelation, while we are not required to pursue any knowledge beyond that.

Although no price is mentioned concerning the sale of Joseph in the Qur'an and the commentaries only speculate from anywhere between 20 to 40 dirham, what is clear is that he was sold for a few pieces of silver which were countable, not weighed, and well below the actual price of a slave. We have already noted that dirham was known in pre-Islamic Arabia and during the advent of Islam, any silver coin was called a dirham. It was also a unit of weight and coinage. It also represented a monetary unit that might or might not be represented by a circulating coin. This makes dirham a word with a multiplicity of meanings. In the light of our study of coinage in ancient Egypt, it is clear that the description of the transaction darhima maddatin (i.e., a few pieces of silver, countable) is accurate. Silver was used in ancient Egypt in commerce, in the form of deben and sh‘t (or sh‘ty) even before the advent of Joseph in Egypt. Furthermore, it was noted that the commercial transactions related to deben and sh‘t of gold, silver and copper involved counting, for example, 24 copper deben for the renting of land as mentioned in the Hekanakhte Papyri. It must be emphasized that since reference is made only to the number of deben that they were of a standard metal quality as well as of a standard weight. Furthermore, the texts nowhere say that either deben or sh‘t were weighed or tested for quality. In the case of dishonesty, the standard was maintained by weighing. It was discussed earlier that inscribed examples of weights from ancient Egypt of this standard were available.

Smith's says that according to Genesis 37:28 Joseph was sold for 20 shekels. This was "about a price of a slave around that time period. So not only does the Bible get the right denomination, it also gets the right currency." There are serious problems with Smith's claims. To start with, in the book of Genesis, Joseph was sold twice; firstly by his brothers "who sold him for twenty shekels of silver to the Ishmaelites, who took him to Egypt" (Genesis 37:28) and secondly, the Midianites who "sold Joseph in Egypt to Potiphar, one of Pharaoh's officials, the captain of the guard" (Genesis 37:36). The Qur'an, on the other hand, mentions only one sale of Joseph to al-Aziz in Egypt by travellers who picked him from a well (12:19-21). Comparing the biblical and the Qur'anic stories, it is amply clear that neither of the two books mention any price for the sale of Joseph in Egypt. But the Qur'an does describe this sale as the one involving a few pieces of silver which are countable. Undoubtedly, Smith has confused himself thoroughly with the stories.

Secondly, the claim that Joseph was sold for 20 shekels being "about a price of a slave around that time period" is not based on data from Egypt because this sale never took in Egypt! If he had bothered to check, he would have found that Professor K. A. Kitchen used the data from the ancient Near East to work out the price of a slave around the time when Joseph lived.[90]