HISTORICAL INVESTIGATION

Smith has claimed that the dirham was introduced after the advent of Muhammad and that it was not created until the time of Umar. This is simply factually incorrect. The pre-Islamic romance poetry of Antara mentions the word dirham.

19. Or her mouth is as an ungrazed meadow, whose herbage the rain has guaranteed, in which there is but little dung; and which is not marked with the feet of animals.

20. Or as if it is an old wine-skin, from Azri‘at, preserved long, such as the kings of Rome preserve;

21. The first pure showers of every rain-cloud rained upon it, and left every puddle in it like a dirham;

22. Sprinkling and pouring; so that the water flows upon it every evening, and is not cut off from it.[3]

Commenting on the presence of the word dirham in Antara's poetry Arthur Jeffery says:

It was doubtless an early borrowing from the Mesopotamian area...[4]

It is clear that the pre-Islamic Arabs were aware of the dirham. The history of the dirham can be traced back to the Athenian (or Greek) coin drachm. Athenian coins circulated widely in the Eastern Mediterranean in the 5th and 4th century BCE. These Athenian coins, once established as the recognised and universal currency, soon became an object of imitation by the people among them whom they had from long use grown familiar. The imitation of Athenian coin types, especially drahm, in Southern Arabia, goes back as early as c. 400 BCE.[5] The Athenian imitation coins were also found in the northern Arabia Felix.[6] Athenian coinage also gave rise to a number of imitative series in Eastern Arabia as well. Excavations at Thaj, Dhahran, al-Khobar, al-Hofuf, al-Qatif, Ayn Jawan, al-Sha'ba, Jabal Kenzan, ed-Dur and Mleiha have yielded lots of coins with many of them being imitation drachms and tetradrachms.[7] Not surprisingly, all the coinage found in these excavations shows the influence of the issues of Alexander the Great.[8] The drachm in Persia was passed on to the Parthian Empire (150 BCE - 226 CE) by the Greek Seleucid Empire (330 BCE - 150 BCE) and when the Sassanid Empire (226 CE - 650 CE) took over Persia, the drachm was known as drahm in the Middle Persian.

The pre-Islamic Arabs were either Persian subjects (in Mesopotamia) or allies (in Arabia). They also handled Persian currency and had a word for it – dirham. The Persian drahm was called dirham in Arabic;[9] and in the former it also meant a silver coin or money.[10] The silver drahm was the main currency of Sassanian Persia. The Encyclopdia Iranica says concerning the dirham.

DIRHAM (< Gk. drakhmé "drachma"; Mid. Pers. drahm, Pers. derham), a unit of silver coinage and of weight...

I. In Pre-Islamic Persia

The dirham retained a stable value of about 4 g throughout the entire pre-Islamic period...

II. In the Islamic Period

For Muslims in the classical period, any silver coin was a dirham, and a dirham was also a monetary unit that might or might not be represented by a circulating coin. A dirham was also a small weight unit, usually not the same as the weight of a monetary dirham...[11]

Similarly the Encyclopaedia Of Islam says about dirham:

DIRHAM. I. The name of a weight derived from Greek dracmn... II. The silver unit of Arab monetary system from the rise of Islam down to Mongol period.[12]

It is not surprising that the Islamic dirham was a logical outgrowth of the Sassanian drahm. The new denomination's very name was an adaptation of drahm, the name for the Sassanian silver piece. Not surprisingly, the Sassanian coinage and the Arab-Sassanian coinage during the advent of Islam were closely related.[13] The earliest Arab-Sassanian coins were struck in 651/2 CE, the year of Yezdegird III's final defeat. The Arab-Sassanian dirhams were close imitations of Yezdegird's issues and were appropriately dated to his 20th regnal year, only adding that they were struck "in the name of Allah".[14] Like the drahm, the dirham was flat and very thin, measuring about 29 mm in diameter and weighing 2.9 - 3.0 gms.[15] Its weight suggested a lowering of standards from the Sassanian drahm which weighed about 4 gms. How does the dirham compare with Smith's highly proclaimed shekel? Concerning the shekel, The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia says:

Shekel, a weight and later a coin, which served as a standard value among the ancient Israelites and Jews. It was apparently based on a standard similar to that of the Babylonians who, as the principal trading people of the ancient Orient, impressed their own standards of currency upon the neighboring nations.[16]

Clearly, both the dirham and the shekel were used as weights and coins. However, the similarities between them end here. The dirham represented any silver coin. It could also be a monetary unit that might or might not be represented by a coin. Resultantly, one must exercise caution when discussing the dirham as it is a word with a multiplicity of meanings.

PHILOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION

It has been recognized by both Muslim and non-Muslim philologists that the word dirham is of non-Arabic origin. For example, al-Jawlq (d. 1145 CE / 539 AH) states in his Al-Muarrab:

And dirham is an arabized form. In the past, the Arabs have used it in their speech. They did not know any other (currency); they ascribed it to Hijra`. The poet said:

In all the markets of Iraq (he takes) a tribute, and in everything sold by any individual (he imposes) a one dirham.[17]

Similarly, al-Khafj says concerning dirham:

(Dirham) Arabized form of daram.[18]

Jeffery says the ultimate origin of the word dirham is from the Greek drakhmé.[19] However, it is not clear how this word passed into the Persian before entering the Arabic vocabulary in pre-Islamic times. It is interesting to note that the Greek drakhmé originally meant "handful",[20] then it was a weight and finally a coin.[21]

SUMMARY

From our discussion, there are three conclusions that can be drawn concerning the dirham.

It was known among pre-Islamic Arabs and the Arabic word dirham came from the Persian drahm.

During the advent of Islam, any silver coin was a dirham and it was also a monetary unit that might or might not be represented by a circulating coin.

It was a unit of weight and coinage.

Given these facts, it is clear that Smith's arguments concerning the first appearance of dirham during the time of Umar and that dirham being just a "coin" are conclusively refuted. Let us now turn our attention to the phrase darhima maddatin, i.e., a few pieces of silver, countable. The Hans-Wehr Dictionary Of Modern Written Arabic defines madd as

ma‘dd: countable, numerable, calculable; limited in number, little, few, a few, some.[22]

Smith's contention here is that only coins are counted and that there were no coins in the time of Joseph – it was bullion that was used for transaction. He then cites from the book of Genesis that Joseph was sold for 20 shekels. If indeed coins were counted and not bullion, it is surprising to see that Smith contradicts himself by claiming that the sale of Joseph fetched the value of 20 shekels, clearly an amount which was counted. Such egregious errors are not uncommon to Smith. Perhaps he is not aware of that fact that bullions had standardised weights which enabled them to be counted. Otherwise currency would not have existed. One would have to barter (and even this would involve some counting!). Any mention of a currency that is not countable is an oxymoron or a contradiction. It is like saying we are speaking a language that cannot be communicated. By definition, a language is communicable, and in similar vein, by definition, any currency system based on weight or paper is countable.

The word madd suggests a small amount of metal exchanged hands, which was countable. How true is that statement from the point of view of ancient Egypt? In order to understand how trade was carried out in ancient Egypt, let us now turn our attention to how metal was used in transactions in ancient Egypt.

3. Precious Metals As A Means Of Trade In Ancient Egypt

In this section we would like to establish certain facts such as the use of precious metals in ancient Egypt, the weights and measures used to quantify the Egyptian monetary system and the evidence for an early "coinage" system in ancient Egypt. This will clearly establish the role of precious metals, and silver in particular, as an important part of business transactions in ancient Egypt. The manner in which precious metals were used will be discussed and then compared with the Qur'anic phrase darhima maddatin (i.e., a few pieces of silver, countable) used in the selling of Joseph in Egypt. Finally, the sale of Joseph as mentioned in the Bible and the Qur'an would be compared and contrasted, highlighting the problems with missionary polemics.

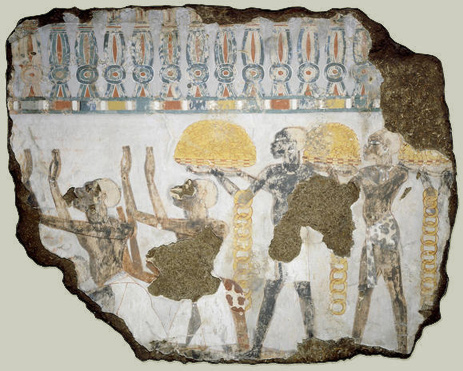

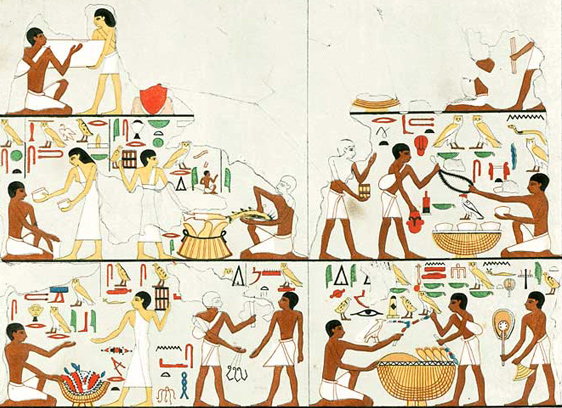

PRECIOUS METALS AS A MEANS OF EXCHANGE

Although there is considerable evidence of an early type of "coinage", it is generally held by scholars that coins were unknown in ancient Egypt before the 26th Dynasty (c. 685 – 525 BCE).[23] Therefore, the prices of commodities had to be expressed in another way. All forms of commerce in ancient Egypt took place in the form of barter, while the value of the commodities exchanged was sometimes also expressed in quantities of copper, silver or gold. While such a barter system certainly existed at the local level it should be considered as part of a larger system in which precious metal was employed as a form of currency. The famous Abydos inscription refers to the traders belonging to the temple and their trade involved precious metals. The inscription reads:

I have given you a ship carrying cargoes upon the Great Green (sea), bring in for you the great [marvels] of God's Land; merchants plying their trade, executing their orders, their revenues therefrom being in gold, silver and copper.[24]

Similarly, Papyrus Lansing from the New Kingdom Period, extolling the life of the scribe compares the scribal profession with others. It says:

The merchants fare downstream and upstream and are as busy as brass, carrying wares <from> one town to another and supplying him that has not, although the tax-people carry gold, the most precious of all minerals.[25]

The scribe here attempted to show the toil of the traders by contrasting the relative values of the metals in which they are said to deal. Since the composition is dedicated to the advantages of the scribal profession, it is simply pointing to the contrast between merchants and tax-collectors, suggesting that the tax people obtained the gold from hard-working merchants.

Another piece of evidence showing that the precious metals such as silver were used in transactions comes from Papyrus BM 10052, again from the New Kingdom Period. Here a legal defence is offered by a woman who was being questioned in connection with silver stolen from tombs. When asked to explain the source of silver in her possession, she explains:

... I got it [i.e., silver] in exchange for barley in the year of hyenas when there was a famine.[26]

last 20 posts

last 20 posts

Similar Threads

Similar Threads

Hybrid Mode

Hybrid Mode